Earlier this Spring when it was still brisk and Covid was ravaging New York City, my partner and I took periodic walks through Greenwood Cemetery near our home in Brooklyn. Perhaps macabre given the circumstances, the cemetery was nearly empty and was peacefully quiet, save for the robins and the cardinals doing their mating thing. I had downloaded the cemetery’s guide to famous grave sites and we made a point to visit a few of them. I was struck at how humble some of the headstones were. From the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat to the mid nineteenth-century Gold Rush dancer and adventuress Lola Montez who was once revered but now obscured by the veil of time. Most of these headstones simply had the name and a birth/death date. There was something disturbing about the ordinariness of a forgotten headstone of a once-famous person. Knowing that covid could take me at any moment and that I would become dust in the wind of forward progress made my throat feel dry.

However, there were a few gravesites which had these little brass flaps that upon lifting revealed a visage of the departed. The photos were often traditional having been taken at a studio like Olan Mills or by a high school portrait photographer, but my favorites were the ones taken with a disposable camera by another family member freezing the deceased loved one at their best moment. The nature of these particular images was how their family and friends had decided to remember them. I was immediately struck by how powerful a single photograph can be in transcending death. While it’s obviously not immortality in the truest sense of the word, simply placing a photo on someone’s headstone is enough to propel the departed’s likeness into the future. If we do “live on” in the memories of those who love us, who’s to say why we can’t live on as a new memory in a total stranger enamored with our portrait? I still can’t get some of these people out of my mind. How bizarre is an unrequited desire for kinship with someone who lived five generations ago?

At some point on our dawdle through the cemetery, I randomly noticed a headstone that had the longest epitaph I’ve ever witnessed. Upon further inspection I realized that, although not on the tour guide’s list of dead celebrities, this was the grave of none other than the famed chemist and photography pioneer Dr. John W. Draper. His name might not be familiar to most, but he was kind of a big deal in the early days of photography (conflict thesis notwithstanding).

Draper was an accomplished chemist and contributed some of the seminal research behind radiant energy and chemical photography exploring topics like incandescence, fluorescence, and phosphorescence. His fascination with the relationship between the physical world and rays of light led his research from photosynthesis to photochemistry. He used novel methods to produce the first clear Daguerreotype portraits of the human face and captured the first successful photographic image of the moon. The earliest known photographs to have ever been taken of a woman were of Draper’s female assistant, although the images did not survive (nor apparently her name). Anecdotally, Draper asked his assistant to cover her face with baking flour in order to increase image contrast. However, the first popularly recognized photograph of a woman was Draper’s sister Dorothy Catherine Draper seen below wondering if the hat was too much.

Dorothy Draper

What I find most striking about this photograph, besides her admirable posture, is Dorothy’s resolute gaze that reaches through time and gives us a tiny bit of her personality. In a sense, a part of Dorothy is right here in this image. Historical documents indicate that at the time this photo was taken, society had a significantly different psycho-spiritual relationship with photography. What was once wondrous and sacred is now ubiquitous. Imagine being Dorothy in that moment, sitting perfectly still and staring into a strange one-eyed box for sixty seconds while your likeness was recorded and stored forever on a steel or glass plate. There are still cultures today that believe in the spiritual consequences of portraiture, and it’s early photographs like this that make it easy to understand why. After all, when one takes a photograph, we often describe this as having “captured” a subject or a moment. Photographers would own the rights to the image (and still do) so that their customers would have to return and pay to reproduce a copy of their essence to share with loved ones.

While the Draper siblings were experimenting with photography, Charles Darwin was writing On the Origin of Species. The emergence of seemingly magical wonders like electricity and photography coincided with a new and exciting theory on human evolution. While Western society was coming to terms with its own spiritual mortality, science was offering a novel opportunity for immortality. Perhaps it was this early experimentation with such a powerful technology that, much to the religious Dorothy’s chagrin, eventually led her brother John to write a controversial book entitled History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science.

As much as I like Dorothy’s portrait, I would rather see the test images of Dr. Draper’s photo assistant. Come to think of it, it’s likely that she would prefer not to be remembered in history as the woman with flour on her face. Besides, I would also think it unlikely that a gentleman of the 19th century would expose a woman in such a way as to not exhibit her beauty. Even today, camera tests most often utilize a female as a studio model. While color charts and random everyday objects provide us with a solid objective understanding of a photographic system’s ability to render accurate color, human skin is the ultimate subjective test. I explain this qualitative phenomenon in detail in our recent article titled: Skin Tones – The Guiding Star to Good Color.

What has to be noted, though I’m not the first to do so, is the prevalence of women as camera testing subjects. This has been my personal experience as having worked in the camera department for fifteen years as well as having watched hundreds if not thousands of camera testing videos (over 15-20 years). One would assume this is due to the over-representation of males in the trade, although I don’t have the time for another research project to verify any sort of correlation. Although if I did have the time, I might start with the recent employment data set published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ which outlines the demographic breakdown for various trades including many in the film and television industry.

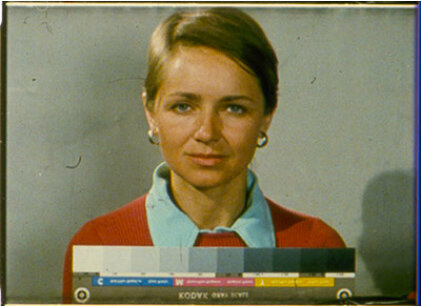

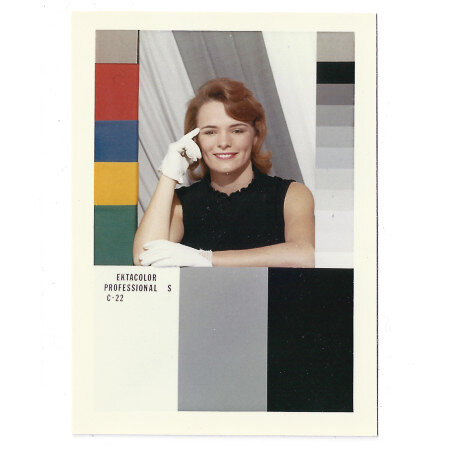

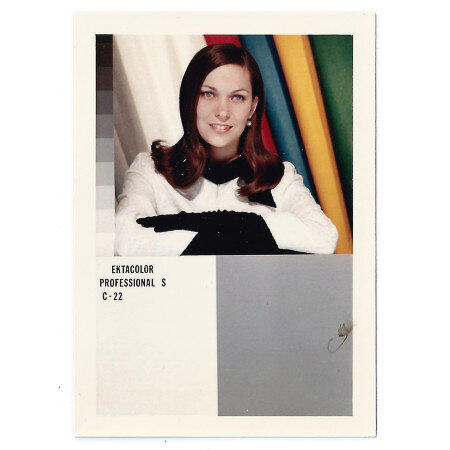

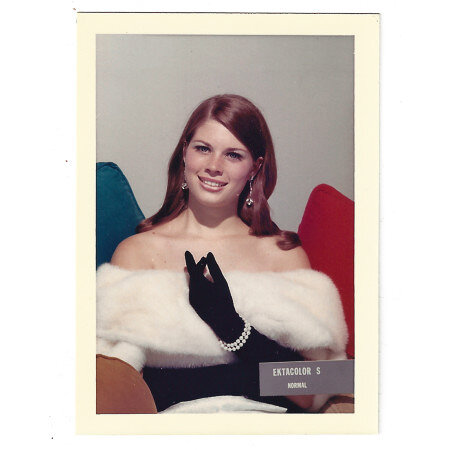

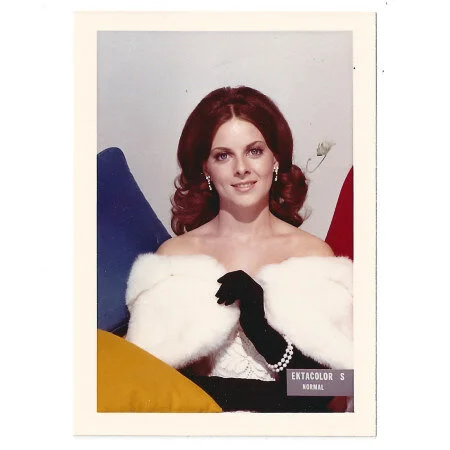

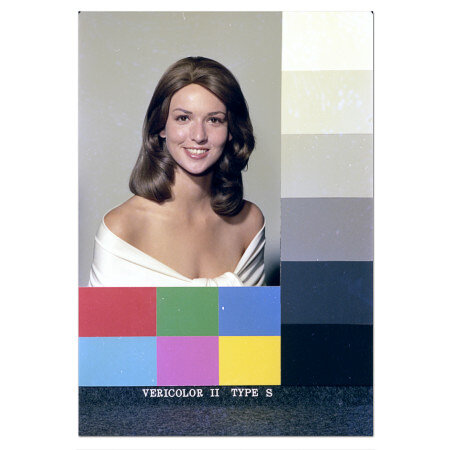

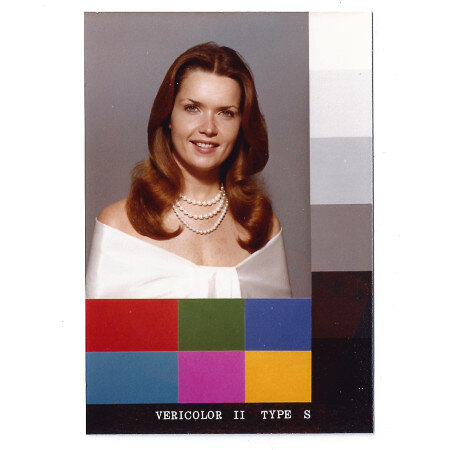

In the mid-twentieth century as color film was quickly becoming the preference for middle-class citizens, Kodak began to hire studio models for their product brochures. One of the first women to model in Kodak’s testing studio was named Shirley Page. She somehow set the standard for Kodak’s concept of beauty, and with that a new tradition was born. Almost every skin tone chart made by Kodak that I’ve been able to find dated between 1950 and 1990 is an image of a woman. Once Kodak was forced to allow small businesses around the world to develop film locally, Kodak would send these high quality prints to each lab in an effort to help them calibrate their machinery and chemical baths using both the gray scale as well as the more qualitative metric of flesh hue. For decades, the Shirley cards were shipped to tens of thousands of labs and became familiar faces to photographic professionals worldwide. Today, color management and printing is almost entirely digital and the Shirley’s of a bygone era have been relegated to oddity collections and archives.

Shirley Page

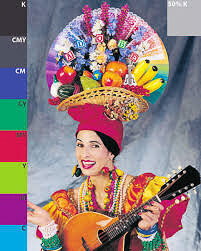

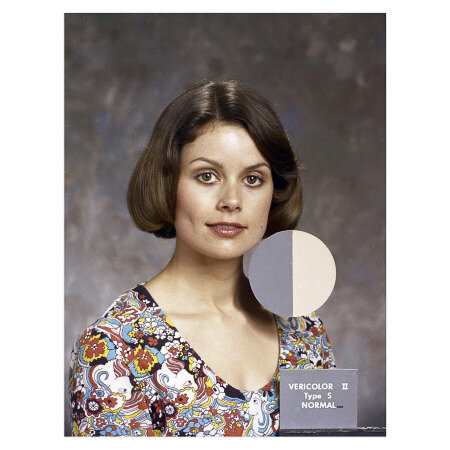

It wasn’t until the seventies and eighties that Kodak started hiring non-Caucasian Shirley’s. It was often multiple women of varying ethnicity straight out of central casting on camera at the same time in order to reflect a more multi-racial global customer and a film stock that had the dynamic range to accommodate the non-white “Shirleys” out there in the world as well as accurately rendering individual skin color. The fact that Kodak labelled these Caucasian test images as “normal” reveals the limited scope of cultural perspective that the company was providing for decades. Even more interesting is how the subjective concept of beauty is ever-changing and always squeezed within the confines of the dominant culture that manifests it.

Kodak Multi-ethnic Shirley card

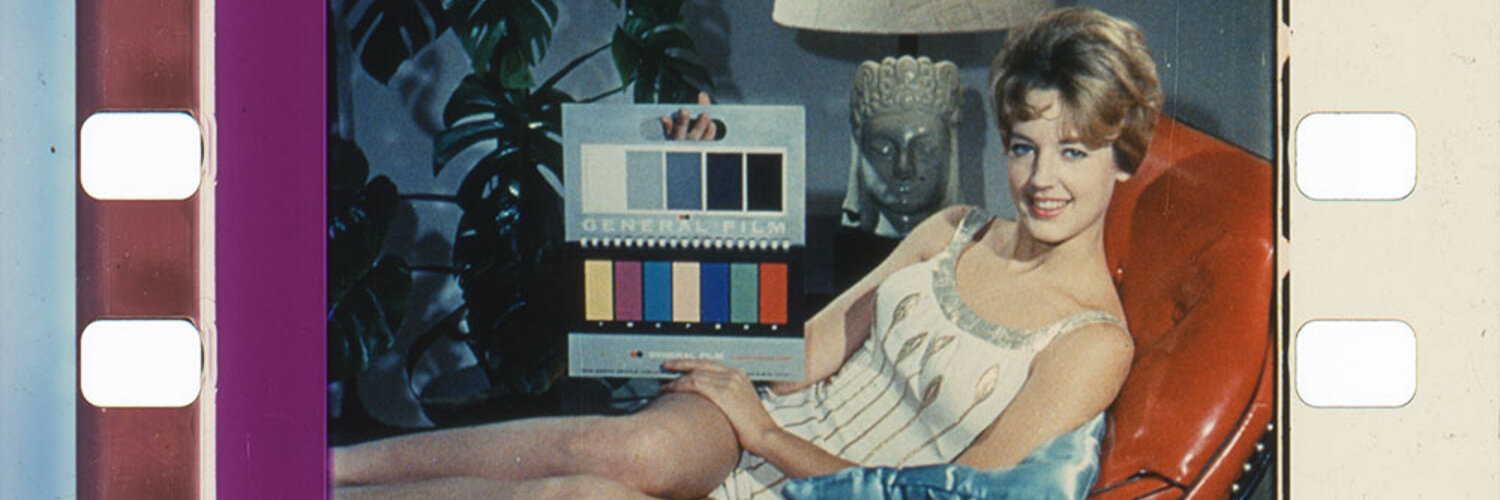

The motion picture industry has been using women on camera since the late twenties for the purposes of calibration. The colloquial term in the industry for these women is a “leader lady” as they were often a 2-4 frame blip in the film leader seen holding a color chart. I’ve also seen them referred to as “flicker chicks” or “Shanghai girls”, although this may just be a term for the weird subculture of film oddity collectors. Slightly more PC terms such as “projector girls”, “Kodak Girls”, LAD Ladies (laboratory aim density), or simply “The Group” have also been used within the industry.

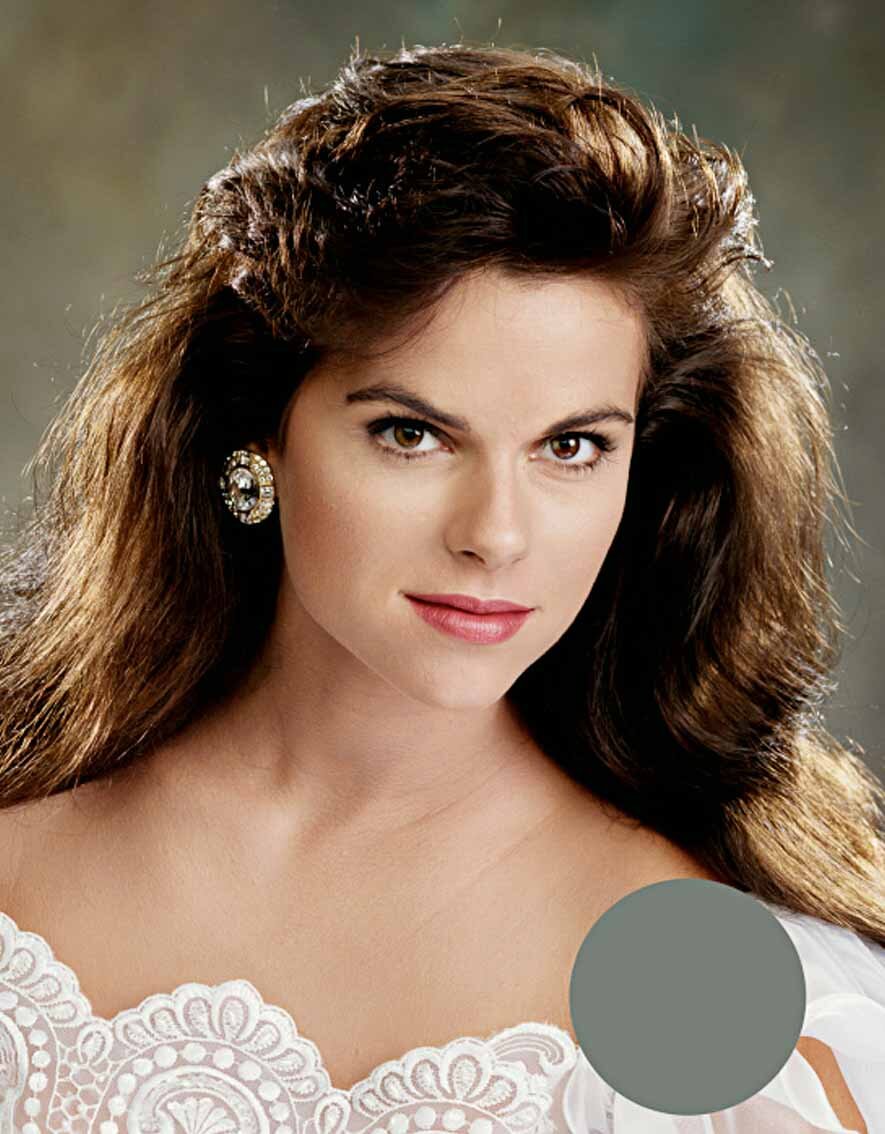

The BBC, as methodical as they are with motion picture engineering, couldn’t miss out on the opportunity to set their own standards. Various BBC test camera charts can be produced upon request from several online vendors today. Here’s one example of a production description for the famous flesh tone test chart known as BBC Test Card 61 featuring the portrait of a woman by the name of Lynn Holmes: “The flesh tone test chart is designed for evaluating the flesh tone rendition of electronic cameras. The chart developed by the BBC London is a four color offset print. The spectral remission of the flesh tones approximates the natural flesh tone very well. (BBC approved)” I might be projecting, but there’s something about this Lynn’s expression that reminds me of Dorothy Draper’s portrait nearly a century earlier. It’s almost as if she were aware of the timeless nature of her situation. Fifty years hence, this image is still used in some software to aid in camera and display calibration. Below is an excerpt from an article written by Image Engineering USA on the history of Lynn’s portrait for the test chart:

“ At first the plan was to take a picture of one of the engineer’s daughter for the chart, but she had red hair. They tried a wig to cover the hair but then the skin tone no longer looked natural. So they had to find somebody else. And there she was, a girl who had worked in different areas within the BBC. She started in a secretarial training course, worked in TV training, in the Drama Department and finally as a producer’s assistant. Having participated in the Miss England contest, Lynne was – and still is – a good looking woman and her natural appearance with dark hair and just the right skin tone made her the natural prospect for the flesh tone chart.”

You can still download the published white paper which provides a colorimetric analysis of test chart 61 on the BBC website today.

Lynn Holmes - BBC flesh tone test chart 61 (1977)

Additional Shirley Cards

References

Images, Information, and Meaning – Claire Lehmann

Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity – Dr. Lorna Roth – Canadian Journal of Communication

Dear Shirley – A photo essay on the Shirley card by Terrence Phearse – Documentary Photographer

Believing is Seeing (Observations on the Mysteries of Photography) – Errol Morris

How Kodak’s Shirley Cards Set Photography’s Skin-Tone Standard – Mandalit Del Barco – NPR Special Series

Kodak Shirley’s – A collection by Hermann Zschiegner – Photographer and Architect

To Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light – Broomberg & Chanarin – Artists

Then and Now Photos of Carole Hersee – Vintage Everyday

Kodachrome Dream – Claire Lehmann

A Brief History of Color Photography Reveals an Obvious but Unsettling Reality About Human Bias – Maz Ali – Upworthy

Shirley Cards of Yesteryear Once Set the Tone for All Color Photos – Rose Heighelbech – Dusty Old Thing

A Bevy of Unknown Beauties – Ken Gewertz – The Harvard Gazette –